Since 2014, questions about China's future have begun moving from the economic toward the political. The question is no longer whether its growth model based on low-cost exports and investment is sustainable; rather, it is whether and how the government can maintain political order as the economy shifts. In short, can the Chinese government and the Communist Party adapt quickly and effectively enough to China's new economic reality to stay in power?

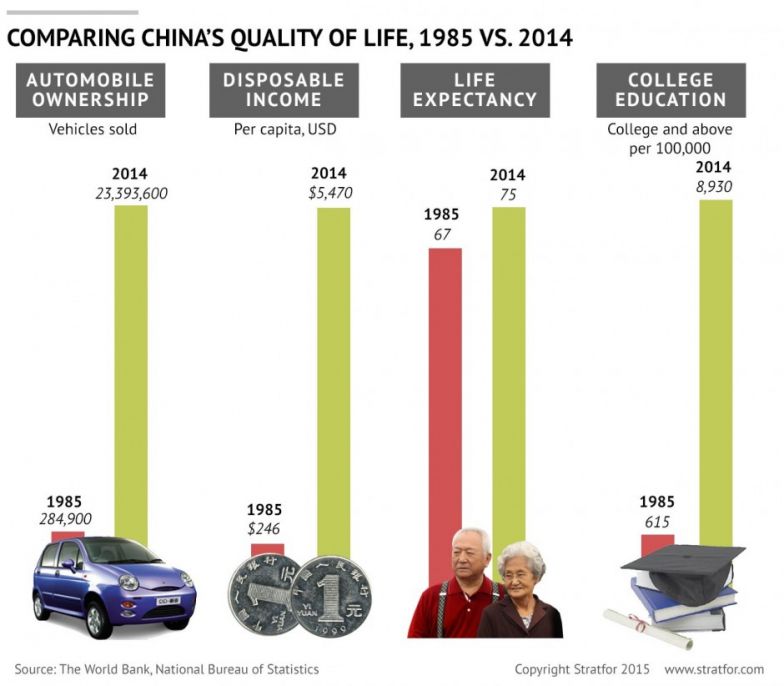

China's leaders are now embarking on a period of political reform against a backdrop of profound social and economic change. The Communist Party's fundamental goal in implementing political reforms is to ensure the continued legitimacy of its rule. For decades, that legitimacy rested on the promises of universal employment and a moderately wealthy society enabled by China's economic boom.

As long as the government met these conditions for the majority of the population, many of the problems, inefficiencies and inequities in China's governance could be — and largely were — overlooked by its populace with the assumption that they would eventually be corrected. But with the economy's slowdown, these promises are becoming increasingly untenable. This process has forced China's leaders to seek new foundations for the legitimacy of their government and the Communist Party's control over it.

What the current efforts for political reform point to is a broad consensus among China's leaders that the future legitimacy of their rule rests in their ability to provide what political scientist Francis Fukuyama calls high-quality governance. This involves the state's ability to collect and fairly redistribute income along with institutions' ability to operate with a large degree of freedom from political interference. Faced with an increasingly well-educated and urbanized consumer society, and pressed by the need to compete globally as a producer of high value-added manufactured goods as well as financial and other services, Beijing needs to implement a variety of measures to govern effectively. Not only does Beijing strive to increase quality of life (for example, by improving air quality, food and workplace safety, and ordinary citizens' ability to earn returns on their savings), it also seeks to incentivize industrial upgrading, innovation and entrepreneurship. The former goals are difficult enough, because they will almost certainly impose higher costs on the state-owned banks and enterprises that remain the backbone of China's economy. But incentivizing the kinds of investments and industrial upgrades that stimulate economic growth will require much more profound changes to China's political institutions, not to mention its education system and business climate.